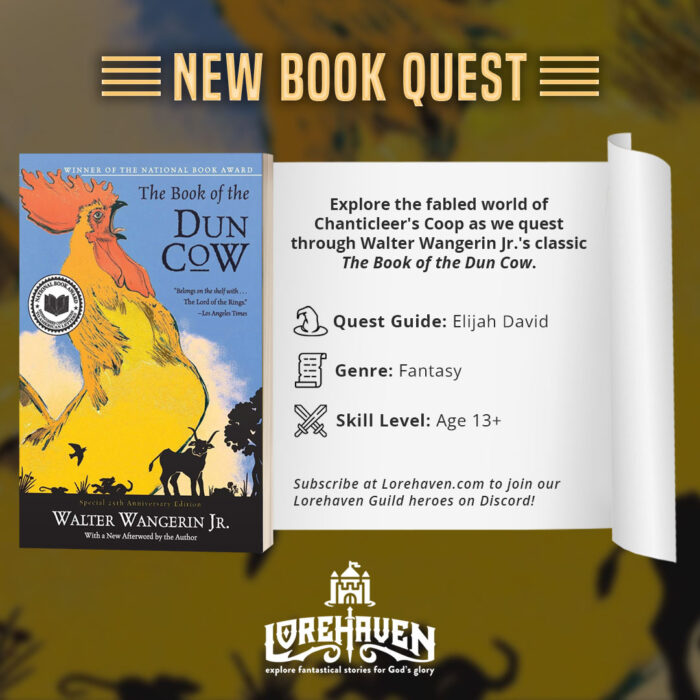

Is Secular Fiction Better Than Christian Fiction?

Some of my Christian storyteller friends share legitimate protests against Christian fiction clichés. These include: Christian fiction is too “clean,” legalistic, unrealistic, and narrow.

Despite market downturns, many authors do well. But for various reasons, some do not.

In response, these authors might say, “All those moralistic rules are why I gave up trying to write for the Christian market. Instead I will take my chances with secular publishers.”

As the proverb goes: out of the frying pan, and into the fire.

I say this because from what I’ve seen, some secular publishers may not actually be more free than Christian publishers. Based at least on accounts that have risen to the top,1 it sounds like secular publishers are taking a page from stereotypical Christian publishing. They are increasingly restricting content based solely on religious (not “neutral”) beliefs.

I say this because from what I’ve seen, some secular publishers may not actually be more free than Christian publishers. Based at least on accounts that have risen to the top,1 it sounds like secular publishers are taking a page from stereotypical Christian publishing. They are increasingly restricting content based solely on religious (not “neutral”) beliefs.

Let’s survey three unbiblical notions in Christian fiction, and then each secular “imitation.”

Christian fiction: ‘You can’t say bad words’

Splickety Publishing founder/editor-in-chief Ben Wolf recently offered five thoughts in this infamous issue. He emphasized an author’s purpose compared with common Bible texts.

Splickety Publishing founder/editor-in-chief Ben Wolf recently offered five thoughts in this infamous issue. He emphasized an author’s purpose compared with common Bible texts.

Advocates of the no-fiction-swearing rule seem to apply these common verses not only to a Christian’s personal behavior, but to writing or reading about fictional characters who do swear. They seem to suppose that merely seeing letters on the page will provoke a typical reader to imitating the character’s sinful attitudes that provoked the verbal outburst. (In biblical texts such as Mark 7, Jesus teaches the more frightening truth about sin’s origin.)

Secular fiction: ‘You can’t say bad words’

Meanwhile, secular fiction also increasingly restricts certain “bad words.”

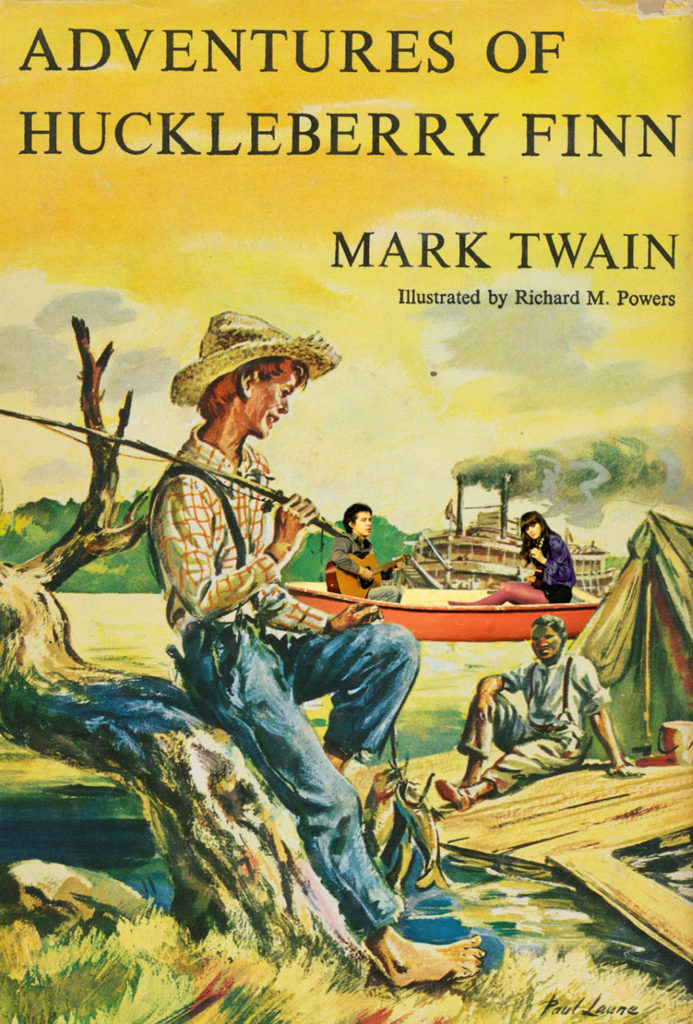

People often restrict books that acknowledge racism, even if they don’t endorse it. We’ve heard debates over whether schools should allow students to read Samuel “Mark Twain” Clemens’ The Adventures of Tom Sawyer or The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.2 Less challenged are some very evangelical-sounding assumptions behind this battle: that just seeing any bad word on a page could make a reader commit sin.

Older generations blocked books’ references to sex, but allowed names or other bad words. Today, those previous allowances/taboos have been exactly reversed.

Christian fiction: ‘You can’t explore particular themes’

Arguably, the Christian fiction no-bad-words rule is also applied to certain themes. Most Christian novels I’ve read don’t want to concede that Christians have denominations—and can get very loud about them. Deeper doctrines are off-limits too, like “Reformed” ideas (e.g., God gives special grace to elect those whom He freely chooses to save) versus more “Arminian” ideas (e.g. God provides grace to people who must freely choose salvation).

Christian publishers may want to “be all things to all people,” as much as possible. They may also want to avoid offending many special interest groups. After all, God’s word says to think about pure things avoid triggering (or “causing to stumble”) everyone, right?

Secular fiction: ‘You can’t explore particular themes’

Author Nick Cole explained why he was forced to publish independently, after his already-sold manuscript included a story element that Harper Collins editors deemed too negative of abortion. Meanwhile, a featured author at Tor.com blasted C.S. Lewis’s The Horse and His Boy for supposed sexism, particularly Hwin the mare, who was suffering “repression.”

Author Nick Cole explained why he was forced to publish independently, after his already-sold manuscript included a story element that Harper Collins editors deemed too negative of abortion. Meanwhile, a featured author at Tor.com blasted C.S. Lewis’s The Horse and His Boy for supposed sexism, particularly Hwin the mare, who was suffering “repression.”

And of course, there’s the apparent trend of publishers hiring “sensitivity readers.”

Secular publishers, too, want to “be all things to all people” as much as possible. They also want to avoid offending many potential interest groups (or the perception thereof).

Christian fiction: ‘You cannot question our fashionable religion’

I say this cautiously, because there’s a whole industry of Christians (real and otherwise) who literally turn a profit by selling their own Doubt and Authenticity. At the same time, it would help to see more Christian characters directly, blatantly, and honestly wrestling with doubt and despair. Like the Psalmists. Like people who want to curse God and die.

Most Christian fiction I’ve read seem to circumvent this. The problem isn’t their lack of doubting characters. Instead, the Christians’ doubts are so deucedly simple. (“Why did God let my wife die?”). Or the skeptics’ doubts are easily answered. (“Yes, God really loves you.”)

By contrast, the Bible endorses complex doubts on the way to resolving them. The Psalms are full of these. The book of Job is all about this theme; it concludes with Job’s restoration.

Secular fiction: ‘You cannot question our fashionable religion’

Meanwhile, secular fiction holds just as sacred a series of unquestioned religious values:

- Progressivism: thou shalt not question global warming or environmentalism.

- Scientism: science isn’t used for evil, but in fact will “save the day” (like Bill Nye!).

- Particular agnosticism: thou shalt not, by incident or intention, assume the existence of a God who has good, absolute authority over human lives, especially sex lives.

- Sexualityism: thou shalt not say that “gay” sex is anything other than wonderful.3

Secular stories are allowed to be “agnostic” on some of these religious points. But, with very few exception I’ve seen, they are not “allowed” to directly challenge these beliefs.

Spiritual sickness vs. spiritually dead

Do I mean that secular publishers are actually worse than Christian publishers? Do I mean it’s all relative and Christian authors had best stick with the devil they know?

In either case, not at all.

However, it does seem strange to pretend secular fiction markets will be less restrictive than Christian fiction markets. In either one, humans are going to human. Either will be religious and/or restrictive. Either will offer certain freedoms and limits.4

It also seems strange to imagine that secular editors, who are not simply “neutral,” will help Christian authors flourish. In any case, the author will likely need to choose, not whether to compromise, but how to compromise. Which can you give up: bad words, or other beliefs?

But in the end, I do wonder about one last market difference. Many godly Christians work in secular media and publishing. Aside from them, which of these is simpler: 1) efforts to cure the spiritual sickness of legalism and anti-excellence notions in Christian publishing, or 2) help resurrect spiritually dead hearts of non- or anti-Christians in secular publishing?

Christian authors can strive to do both, in whatever sphere God has called them to serve.

- This presumes these stories are typical. I’m open to the possibility that these are extreme cases, notable mainly because they are rare, and do not represent the mainstream of secular publishing. For several of these links, I must credit Mike Duran for rounding them up. ↩

- Example: this CBS News article. ↩

- None other than Doctor Who showrunner Steven Moffat seems to have violated this rule in his last episode. This one featuring none other than already-famously “gay” companion Bill. Spoilers: Moffat’s story introduces Bill and her rapid attraction both to the Doctor (on sabbatical from his traveling) and to another woman. But the woman is soon killed and possessed by a liquid-based alien that can show a person’s own reflection (though not mirrored). The creature then makes false promises to show Bill wonders across the universe, in a darker version of the Doctor/companion relationship. In the end, Bill declines the creature’s advances and joins the Doctor. ↩

- But as I’ve previously suggested, a novel set in a sex dystopia, showing the darkness of today’s modern sexual experimentation, would not pass muster with either market. ↩

Tangent: Heck, I’d read a story about Hwin as Boss Mare. I don’t think “repressed” is the right word for Hwin, but Lewis didn’t really bother giving her much of a character, which is a pity. It’s pretty light criticism for Narnia, tho; Ana Mardoll is a lot meaner/less forgiving.

Also this isn’t a Natsume Yuujin-cho review, the sixth season just started and I haven’t gotten to gush about the earlier ones yet. Is it because it’s shoujo? It’s a lot slower-paced than your typical shounen, but it has a nice, calming atmosphere. I mean, if you had trouble explaining Pokemon to Grandma and her church lady friends, this isn’t gonna be any easier, but I can’t see either of my grandmas understanding why I watch cartoons at my age anyway.

Yikes, yes. Ana Mardoll’s views on Narnia are crazy-scary. I think she was my first encounter with an SJW.

I sort of liked Hwin’s character. She was nice and timid and caring, and a softer being like her was good for balancing out other characters in the story, like Aravis, who is tough and cool yet has a kind side to her. Or Bree, who was kind but was more firm and tough by nature. It’s a little sad if people want to dismiss Narnia as sexist. Some characters say sexist comments, but the book itself contains many strong female characters, (If I recall correctly Lucy was said to go out into battle with the men) And I suspect these strong female characters went against the grain of how women were often perceived in some cases around the times these books were written. In a lot of ways it can be seen as pioneering feminism a bit.

As far as Hwin not having much character development…Narnia wasn’t a super detailed book in that respect. A lot of characters didn’t get much development except for a few major ones, and I think that’s more about the style the series was written in.

BTW, notleia, would you be interested in being a beta reader? I don’t have anything written complete enough for betas yet, but I’m trying to be on the lookout for possible beta readers.

I’m game for beta reading, but I feel responsible for warning you that I can be pretty mean because of my SJW-flavored training in elitist literary snobbery. Let the buyer beware.

Alright, I’ll keep that in mind 😛

Do you mind reading stories that have animals as the main characters(ones mainly aimed at teens and adults) or do you only like stories that center on humans or a mixed cast of both human and animal characters?

I’ll probably read any of it, tho come to think of it the last wholly animal-centric story I read was Watership Down. Or maybe one of those Warrior Cat books that I don’t care for as much, but it’s not really because of the main characters being animals.

All this is part of why I am going to publish my own stories, rather than try and leap through the hoops of secular or Christian publishing houses. And really, these issues aren’t directly a matter of whether someone publishes in the Christian Fiction genre or not, it’s a matter of where someone gets published or who they are trying to sell to. Plenty of my stories will be Christian fiction, but will still have violence, mild curse words, and deal with a lot of heavy topics.

Definite food for thought.

Your closing statement really speaks to me. God calls some Christian authors to the Christian market and others to the secular market, and neither calling is higher than the other.

Thanks for writing this.

I’m an indie and I write Christian fiction. Four books on Amazon. My last book was the most fun I’ve had writing. The main character (an abused woman) denied there was as God, even calling him a murderer, and I got to rack up a body count(9). Then I got a nasty gram on FB saying that I couldn’t be a Christian because I wasn’t giving my books away for free.

Your last sentence “Christian authors can strive to do both, in whatever sphere God has called them to serve.” was very freeing for me. In my ‘real’ world people question God, deny him, and bad things happen to good people. It seems to me that current Christian Fiction is usually so often removed from reality. People don’t just become Christians just because you said “Jesus Loves You”. There’s a process and it’s often times painful. My fiction world reflects a lot of my life (sans body count). I’ve seriously been thinking about not writing Christian Fiction any longer if only because the longer I’m with it the more disappointed I get with it. I think I can write a decent secular fiction and still maintain my faith.