‘The Secret Of Kells’: The Shape Of The Light

“I have seen beauty thrive in the most fragile of places.”

There’s something about the dusk.

Twilight. Evenfall. Magic hour’s afterparty. That fleeting interval of fading, of illumination absent its source. The sky bleeds out, the darkness swells, and sight burns borrowed time. The night is nigh, and every instant precious. We know we have not long.

Perhaps it’s this sense of urgency that compels us to call it beautiful. Scarcity imputes value, after all, and there’s no recalling the sun. In the heat of the day, light is everywhere. We don’t dwell on it because we don’t have to. But when shadows stretch and the sky begins to blush with parting-thoughts, we awaken to our submersion. We suddenly see light as if for the very first time. And we wonder at its beauty.

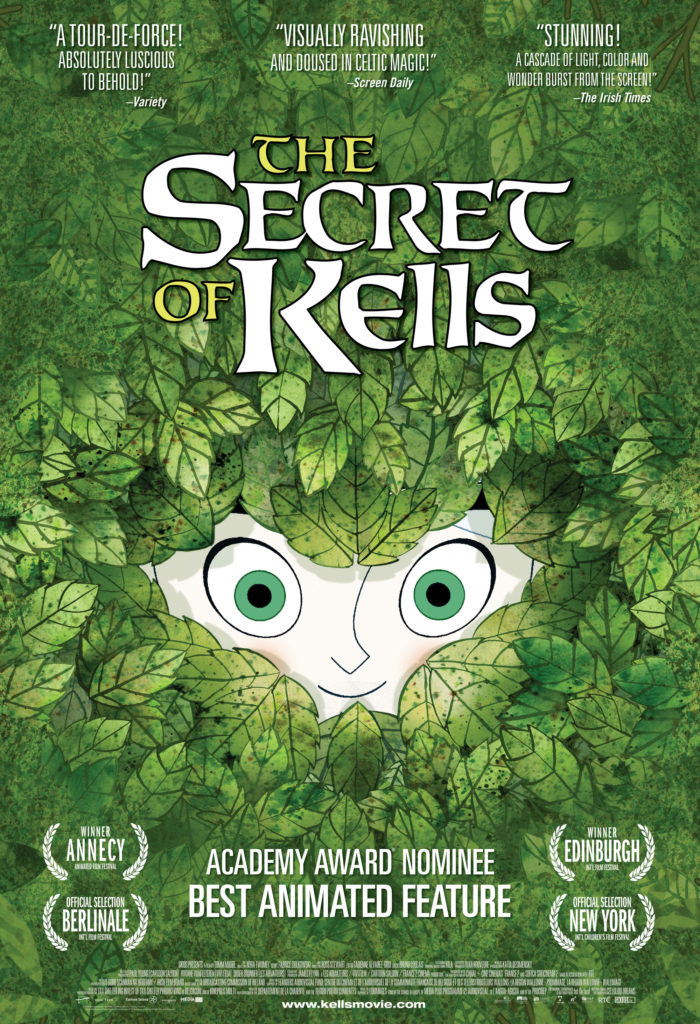

Beauty is the one thing I knew to expect from The Secret of Kells, a 2009 animated tour de force from Irish directors Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey. I’d heard how its visual aesthetic was that of an illuminated manuscript, and its look and feel proved even more original than I’d imagined. A medieval scent wafts from its strong lines and deep colors, permeating an environment built from abstractions, perceived with imperfect perspective, and enriched with Bruno Coulais’ ravishing score. It’s a style both fresh-faced and ancient, an appeal to artistry not seen for centuries. But what I hadn’t anticipated was the film’s deep beauty — a lyric poignancy that left me speechless, eyes streaming.

“The work of angels.”

Here, the eyes we see through are those of Brendan, daydreaming nephew of a ninth-century Irish abbot doing his somber best to fortify the Abbey of Kells against the coming Northman nightfall. Brendan is kind, joyful, and curious — intrigued by the surrounding forest into which he’s forbidden to venture. But he’s also obedient, so it takes an exceptional enticement to goad him beyond his uncle’s rising wall: an enticement that arrives in the form of Brother Aiden, legendary illuminator and refugee from sacked Iona. Eager to assist Aiden in his work, Brendan enters the forest to obtain oak galls for ink-making. At stake is the completion of the Book of Iona, an illuminated gospel so glorious it “turns darkness into light.”

In the ancient forest, amid a ring of stones, Brendan encounters a fey sprite out of fairytale. Her name is Aisling, and their rapport, as effortless as it is unlikely, unveils to Brendan a hidden world of wonder in the heart of the pagan woods. “You will learn more in the woods from trees and rocks than from any other place,” says Brother Aiden. “You will see … miracles.” The beauty of creation teaches Brendan this is true.

Threshold of wonder.

There is an innocence about Aisling that recalls the “noble paganism” C.S. Lewis famously found so attractive. Mischievous without malice, she revels in the freedom afforded by “her” forest — freedom to celebrate beauty and strength for their own sake, without concern for the welfare of others. In the words of Dr. Dimble in Lewis’ That Hideous Strength, “There used to be things on this earth pursuing their own business. They weren’t ministering spirits sent to help humanity, but neither were they enemies preying upon us … all the gods, elves, dwarfs, water-people, ya, longaevi.” This is Aisling’s world — a world of childlike ignorance veiled in mist, or dappled by half-light within a sea of leaves. She knows not God, yet rejoices in what He has wrought. And it is by instinct that she, too, falls in love with the work of beauty Brendan wishes to bring forth.

“This is my forest.”

But the Abbot of Kells is also right. There is great peril in the world outside, and civilization hangs by a thread. From its den of darkness, the dread deity Crom Cruach shoots forth tendrils of terror. Brendan will learn the hard way that this evil is not imagined. But darker still looms the northern scourge. The Vikings themselves are portrayed as a force of nature — implacable, inhuman, mindless as a wave of night that will sweep all before it. “Pagans, Crom-worshippers,” growls the abbot. “It is with the strength of our walls that they will come to trust the strength of our faith.”

The Abbot and his plans.

His is a joyless optimism: in order to save civilization, the Irish must abandon its freedoms and its fruits, bending their efforts instead toward defense. Aiden and Brendan are scorned for their artistic pursuit while the great wall stands unfinished. Aiden, for his part, has already given up, at least in the short term. “No wall can stop the Northmen,” he says with uncharacteristic solemnity. “When they come, all we can do is run, and hope that we are fast enough.” His is a pessimism that leads not to despair: “There’s nothing in this life but mist,” he murmurs, and yet the mist of his life has been devoted to the Book.

The Book of Iona is that which unites all good parties. Brendan, Aiden, Aisling, even the abbot himself, indirectly. It is beauty created for its own sake, the fruit of civilization, a glimpse of heaven on earth. Without the Book, the Wall is worthless. Without the Wall, the Book may yet live on.

When the sun is high, we take its pervasive light for granted. As it sets, the shape of its light is defined. In the same way, civilization’s twilight reveals the true nature of what is slipping away. It is this overdue existential clarity that cries to me so powerfully from the works of Tolkien and Rosemary Sutcliff, and that unlocks the gate of my tears as The Secret of Kells guides me gently through the grief of needless loss. In the words of young Torhthelm in The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth, “So men flicker and in the mirk go out. The world withers and the wind rises; the candles are quenched. Cold falls the night.” Truth, goodness, beauty — these are what our walls encircle. We protect beauty because it is born of truth and goodness, and because it is their proof, but our protectionism is ultimately futile. In the end, death comes for us all. Our hands fly open, our hoards are plundered, our walls lie breached and ruined.

Bad-news ravens.

And yet the Christian’s hope transcends even death. The sufferings of the present time are nothing compared to the glory that will be revealed (Rom. 8:18). Brother Aiden dreams of drawing a droplet of that glory into this present age, of transforming darkness into light, of reflecting a breadth of beauty no wall may contain. To this end he labors, his quiet desperation equal to that of the abbot, his sense of ongoing fulfillment incomprehensible to the more pragmatic man. His is the dream of one whose gaze roams beyond the borders of this world, who is not content merely to safeguard that which is, but yearns for that which one day shall be. It is the dream of Niggle, Tolkien’s longsuffering perfectionist: a vision of beauty too exquisite for human hands to fashion. The unachievable goal.

And yet impossibly, from out of black despair, beyond all hope and longing, Aiden’s dream is realized. And the glory of this, the poignancy, is more than I can describe in words. It is darkness, turned to light. It is the dawn that follows night.

Like the Book whose story it tells, The Secret of Kells is more than a series of pretty pictures, and more than a mere message. An unresolved dissonance pulsates at its core: how shall we preserve that which is good and beautiful in life? How shall we redeem the time? Can our lamps be shielded from the storm, or must we learn to work in the dark? When the clock at last strikes midnight, which of all our doings will survive? This question is of more than theoretical importance: today, in an age of cultural twilight, it’s an existential dilemma that haunts the minds of many. Shall we raise walls, or illuminate books? Ironically, while the Dark Ages may not provide answers, they can inspire hope.

For the secret of Kells is this: that light is greater than darkness, and that it shall return even after all seems lost.

Oh my gosh, this is so beautifully written. I love this film dearly and this review is nearly just as beautiful. Well done. Well done. A film that was made for such a time as this.

Protip to those who haven’t seen it: turn on the subtitles for Aisling’s whispered intro. But at least they’re real Irish accents *squee*!

I’m surprised you didn’t talk about the art more, because it seemed too geometric for illuminated manuscripts. It looks more like an acid trip in a Picasso museum, but even if it takes a while to get used to, it’s interesting.

Honestly, the straightforward story is meh, one we’ve heard a thousand times, but they do it pretty well with monk-who-looks-like-Willie-Nelson.

http://the-toast.net/2015/09/24/two-monks-invent-religious-iconography/

The same studio did another film, Song of the Sea. Worth checking out if you like Kells, especially if you have a good tv and blu-ray player. Beautiful colors, both.

I’m definitely planning to see it, although I’m slightly nervous it won’t live up to its predecessor. Are my qualms unfounded?

I didn’t see Kells so can’t say. Subject matter is a lot different though.